johnt

New Member

Posts: 5

|

Post by johnt on Sept 12, 2014 12:51:22 GMT -8

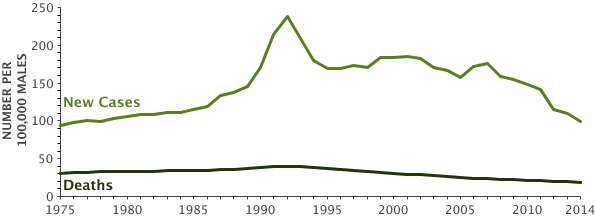

Looking at the SEER data on PC form 1975 to 2011, the following data points are reflective of the overall trend by year. Numbers are per 100,000 men

NEW Cases Deaths % deaths to DXed

1975 94 31 32

1992 237 39.2 16

2000 183 30.4 16

2011 139.9 20.8 15

PC cases increased drastically in the early 1990's and have been decreasing ever since. What caused the significant increase?

The reduction in deaths seems to be almost entirely due to the reduction in diagnosed cases.

In the era of psa testing it would seem that diagnosis would go up, but it has declined each year since the early 90's.

The death rate for those Diagnosed has not changed significantly in the past 20 years despite early detection and the multitude of new treatments.

I hope someone can shed some light on these trends.

|

|

|

|

Post by tarhoosier on Sept 13, 2014 8:04:16 GMT -8

This flood of undiagnosed men discovered using PSA tests accounts for the jump in the 1990's, in my opinion. The numbers settled from there until today, or 2011 in your example. There has also been a change in grading and thus diagnosis during the past 20 years which may limit the rate of diagnosis compared to past years.

The percent deaths may reflect the G8-10 men who have a much tougher time outliving their disease. Even before Dr. Gleason published his grading scale prostate cancer was known as a slow growing condition, with some distinctions.

|

|

|

|

Post by KC on Sept 15, 2014 13:40:56 GMT -8

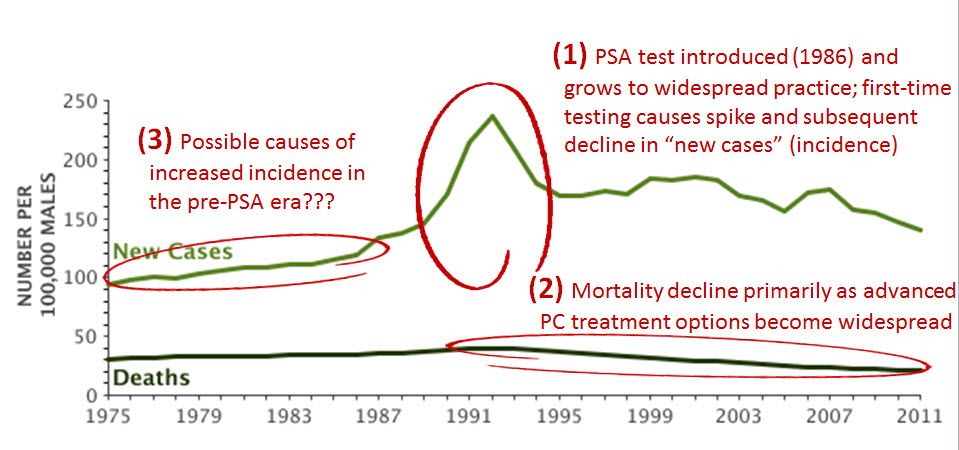

John, this chart has the same SEER data you listed for several sample years. John, this chart has the same SEER data you listed for several sample years.

The very sharp increase, and subsequent drop-off to a new sustained level, of new cases in the early 1990s was from the pent-up demand prior to widespread PSA screening.

Notice that the tipping-point for PC mortality (deaths) coincides with the point at which PSA screening became widespread in the early 1990s. Understanding the “lead-time” phenomena which occurs when a disease screening program is implemented shows that the decline in mortality was driven primarily by changes in disease management practices (as we entered the “golden age” of PC hormone/chemo treatments) and NOT from PSA screening.

The lead-time for a cancer is the length of time by which the date of diagnosis is advanced through screening from the date it would have been diagnosed clinically. A number of variables influence the lead-time calculation including the screening program frequency, age, and grade/stage of the disease, but for a single PSA screening test at age 55 the estimated lead time was 12.3 years in a Vickers study. In other studies, the lead-time using PSA testing ranges from 5 to 14 years (generally shorter for older men).

PSA testing became widespread in the US in the early 1990s. The reduction in mortality occurred too quickly to be attributed to PSA testing. Any additive affects of PSA screening on mortality reduction would begin to show up in the early 2000’s.

{FYI your "% deaths to DXed" doesn't make sense because it is a percent of a percent.}

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen on Sept 15, 2014 17:02:40 GMT -8

KC- I'm totally with you except for the "pent-up demand" part. I'm not sure what you mean by that. I've seen an interesting analysis attributing the PC detection increase in the late 80s-early 90s to the near universal use of refrigeration and the resulting heavy per cap consumption of milk in the US. Freon refrigerators were introduced in the US in the 1930s and quickly became widespread, increasing the use of bottled milk for kids.

I've seen studies that, after lead-time bias correction, attribute anywhere between 24%-40% of the reduction in PC mortality to earlier detection and treatment. I think the 24% is more accurate, but I understand the case for 40% too. There's no doubt in my mind that some younger higher risk people were detected by PSA screening and were curatively treated before metastases occurred. Also, both surgery, radiation, and medication techniques improved, especially in the 21st century.

|

|

|

|

Post by Tony Crispino on Sept 15, 2014 18:55:34 GMT -8

Interesting theory on the "Freon Factor". But also along with Freon we have new deodorant concoctions, hair shampoo's, and lot's of other modernizations to put into that factor.

I really have always wondered why the jump in 1991 when everyone says the "screening" era was later. I don't necessarily agree with the dates of when PSA screening got to be prime time. But I theorize that we had such an initial jump because everyone was unscreened when the PSA era got started and thus a lot of new finds that were removed from the screening pool early. Thus subsequent years found less new cases.

But I do think Allen summed it up well that death reduction is not just PSA screening but a lot of factors including improved treatment options play a role. Whatever the numbers, we still need better tests. Hopefully coming soon...

|

|

|

|

Post by KC on Sept 16, 2014 8:24:28 GMT -8

“Pent-up” demand was my own choice of phrases to describe the “low hanging fruit” (another of my own phrases) which occurred as widespread PSA testing spread quickly and many, many men received their first-ever screening test. Everyone (essentially) was initially getting a “first-time” test starting late 1980s/early 1990s. There were an abundance of untested men with detectable PC in the first few years. However, as the number of first-time tests as a percent of the total PSA tests performed started to decline, fewer new cases were diagnosed (incidence dropped to a new steady-state level).

The association between first-time PSA tests and incidence explains both the increase and subsequent decline and incidence, which was published by Legler et al in a 1998 paper titled “The role of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing patterns in the recent prostate cancer incidence decline in the United States.”

Allen, does this better explain my use of the phrase "pent-up demand?"

How much has PSA screening contributed to the decline in PC mortality? Most feel that there is some contribution, but many feel it's not so much. I already mentioned the "lead-time bias" which would trigger a downward change in slope around the year 2000 caused by PSA screening...but there wasn't much of a change in slope at that time indicating it probably wasn't much impact. What DID happen was that there were substantial improvements in treatment-specific health outcomes among men treated for PC. Further to that point, several European countries who were slower to implemented PSA screening reported declines in PC mortality at the same time as the US...they implemented the treatment-specific improvements, but not the PSA screening.

Lastly--and this is probably the key reason so many oncologists specializing in PC care bypass the PSA test themselves (not for monitoring patients they treat; I'm talking about in their own personal lives)--the biology of PC is such that screening patterns are unlikely to detect the most lethal and aggressive metastatic tumors during the short time they are detectable in an earlier stage.

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen on Sept 16, 2014 9:16:40 GMT -8

Tony, the point wasn't about freon, it was about a generation that grew up on lots of cow's milk that freon-based refrigeration made convenient. Read my post about repurposing somatostatin analogues for an explanation and a link to an analysis of this issue.

KC, I understand what you're saying and I very much agree. The spike of incidence between 1986, when PSA was FDA-approved as a recurrence indicator, and peaking when it was approved for diagnostic use in 1992 and then for screening in 1994 may be explained by the rush to get the new test, even off-label. However, PC incidence had been going up for a long time before that at an average increase of about 3% a year from 1969-1986. This part of the curve remains to be explained.

|

|

|

|

Post by Tony Crispino on Sept 16, 2014 10:38:10 GMT -8

I understood clearly. My "Freon Factor" was not to point the attention to the gas but to the consumption of milk being increased. But then you missed my point. There are a lot of changing things in the world beyond milk. At one of Vogelzangs talks he was asked about why the prostate cancer rates were so low in the Pacific Rim, was the food or the genes the reason? He replied that it could be, but it could also be the products they use or don't use for hygiene or many other things. Pesticides? The way we cultivate our food supply? We don't know these things as facts but we do know that when someone comes out of the Pacific rim to the US and they adopt to western living their chances increase for prostate cancer. Many are quick to jump on diet but as he said we just don't have enough data to jump at that conclusion.

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen on Sept 16, 2014 11:31:18 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by KC on Sept 18, 2014 7:30:54 GMT -8

However, PC incidence had been going up for a long time before that at an average increase of about 3% a year from 1969-1986. This part of the curve remains to be explained.

So far in this thread, we've talked about (1), the spike in incidence/new cases which accompanied the growing, widespread use of PSA testing and the "pent-up demand" of undiagnosed men who received their "first-time" test... So far in this thread, we've talked about (1), the spike in incidence/new cases which accompanied the growing, widespread use of PSA testing and the "pent-up demand" of undiagnosed men who received their "first-time" test...

And we also talked about (2) the decline in mortality/deaths which was probably mostly driven by the rapid succession of drug therapies introduced in that era, which began the "golden era" of PC drug therapies. Lupron was first FDA approved in 1985, and within a few short years became a dramatic game-changer and the new standard of care for men with advanced PC. Zolodex in 1989, followed by Casodex, Nilutamide, Flutamide and Viadur all in the last century...all prior to the "lead-time" bias from PSA testing would have had much effect. Certainly, PSA testing contributed to the decline in a way which is also immeasurable, but the "logical falicy" is to tie the shift in mortality (effect) primarily to the introduction of PSA testing (cause)...the data simply does not witness to that conclusion.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

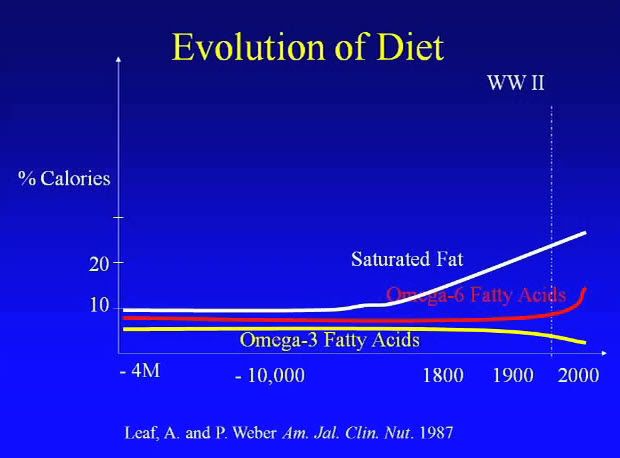

So what drove the increaced incidence/new cases in the period labeled (3), before the PSA era? That's an interesting question, and it seems that there is not a "Red-X" to point to as the one, obvious cause of the 3%/year increase since 1969 which you commented on (or since 1975 as shown in the chart). The association/correlation with the earlier emergence of freon refrigeration and the subsequent growth of dairy products and its linkage to advanced PC cases is fascinating. There are probably other factors unique to the era which also contributed...I'll speculate on a few.

One thing to state clearly before commenting further is that "incidence" does NOT describe the set of men who "have" prostate cancer...it merely describes the subset of men who "have" PC which have also been diagnosed and become a "new cases." As we know, many men are walking around today with undiagnosed PC, indolent (mostly) or advanced, or anything in between. The numbers of new cases reported MAY NOT really be an actual indicator for increased prevalence of PC...it is simply a direct indicator of more cases reported. BUT, there is a corresponding very slow increase in deaths in the same period which may also have some unique attributable factors.

Building on your suggestion of the "freon factor," and recognizing that diet has a strong linkage to PC, the era (3) also follows the rapid increase in refined sugars and early shifts towards more processed foods which many health officials link to the growth of numerous cancers (and other problems). These are recognized as the foods that "feed" cancers. (Have you read the "Anti-Cancer, A New Way of Life" book?)

There is also the interesting (and unanswerable) question of misattribution. This is most commonly associated with deaths--what gets entered on the death certificate--but may have also been related to diagnosis in the first part of the 20th century. There certainly was growing awareness of cancers of all types going into the 60's, and increased sophestication of the medical profession (conntinuously) which changed dramatically over the course of the 1900s.

Anyhow, interesting to speculate on (3). Other ideas?

johnt, haven't heard back from you during the course of this discussion...are these postings addressing your original question? |

|

johnt

New Member

Posts: 5

|

Post by johnt on Sept 18, 2014 18:45:44 GMT -8

They are all plausible reasons. I would bet the increased use of dioxins in agriculture in the 60s and 70s plays some role. The way the death rates are determined, by death certificate, is probably accurate even though it may contain errors. I wonder how the new cases are calculated. Who actually sends in the data on newly Dxed? Is it the initial Dxing doctor, the pathologist or the treatment doctor or is it just data arrived at by sampling? what about Gleason upgrades putting someone in a higher or lower risk category? Is there double counting or many cases that are not recorded. We use this data to measure the effectiveness of our screening and treatments and I have no idea on how it is gathered.

|

|

|

|

Post by KC on Sept 19, 2014 7:03:47 GMT -8

johnt,

You asked a wide variety of questions in your last post. In this reply, I’ve tried address the last two about the process of SEER data collection; you asked:Is there double counting or many cases that are not recorded. We use this data to measure the effectiveness of our screening and treatments and I have no idea on how it is gathered.

John, the contemporary process for collecting SEER data is rigorous and robust. Rigorous and robust does not mean perfect, but the time- and labor-intensive effort make the product (cancer statistics) of tremendous value to researchers, healthcare providers and public health policy makers to better monitor and advance cancer treatments, and improve cancer prevention and screening programs.

The first-ever hospital-based cancer registry was launched in 1926 at Yale-New Haven Hospital. After broader adoption and improvements, the US Congress passed the National Cancer Act of 1971 which mandated cancer care facilities to collect, analyze and disseminate data for the prevention and treatment of cancer. NCI, the National Cancer Institute was formed from this Act, and two years later, in 1973) NCI created SEER as the first national Cancer Registry. The following year (1974) the National Cancer Registrars Association was established which today coordinates the collection of data which is now legally mandated at the state-level. Again, in efforts of continuous improvement, Congress adopted tweaks to the law in 1992 and 1998 which helps fund and standardize the registry practices and procedures through the administration of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

John, you are in Idaho for the summer. You can find, for example, information on the Cancer Data Registry of Idaho (CDRI) here, if you are interested in seeing a state-level program in detail. The CDRI was established in 1969, and became a population-based registry in 1971 (outcome of the National Cancer Act). The CDRI site (via the link I provided) describes the data collection process at a high-level thusly:

Each Idaho hospital, outpatient surgery center, and pathology laboratory is responsible for the complete ascertainment of all data on cancer diagnoses and treatments provided in the facility within six months of diagnosis. Sources for identifying eligible cases include:

• hospitals;

• outpatient surgery centers;

• free-standing radiation centers;

• physicians;

• death certificates; and

• other state cancer registries reporting an Idaho resident with cancer (as negotiated).

When a cancer case is reported from more than one source the information is consolidated into one record.

To assure validity and reliability of data, CDRI uses software that checks the content of data fields against an encoded set of acceptable possible contents and flags the acceptability of coded data. Records are also routinely checked for duplicate entries.

While each state’s laws may be slightly different, the national association of Cancer Registries sets quality standards and requirement for reporting. The link above drills-down into Idaho’s registry, but here, if you are interested, is a table summarizing all 50 state cancer registry laws and requirements.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

A key take-away....by continuing to provide annual life-long follow-up information to our health care providers about residual disease, recurrences or additional malignancies, and subsequent treatments, we “cancer survivors” are contributing to the growing base of SEER data.

|

|

|

|

Post by KC on Sept 23, 2014 11:03:30 GMT -8

Back to the earlier discussion about why there has been an increased incidence/new cases in the period labeled (3), before the PSA era...this slide illustrates some of the radical changes in the human diet in the last century (or less)... Strong linkages have been reported associating Fatty Acids and prostate cancer. Strong linkages have been reported associating Fatty Acids and prostate cancer.

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen on Sept 24, 2014 9:10:12 GMT -8

I don't know how strong those linkages are. They seem rather tenuous and variable to me. Below is the largest and most recent meta-analysis I have seen of all studies that have looked for the association between circulating fatty acids and prostate cancer risk. It concludes, "There was no strong evidence that circulating fatty acids are important predictors of prostate cancer risk. It is not clear whether the modest associations of stearic, eicosapentaenoic, and docosapentaenoic acid are causal." Circulating Fatty Acids and Prostate Cancer Risk: Individual Participant Meta-analysis of Prospective StudiesThere may be other, more important reasons, to control fatty acid intake, but prostate cancer does not seem to be one of them. |

|

|

|

Post by KC on Oct 7, 2014 6:15:56 GMT -8

I was listening to the Diane Rehm show this morning while driving to work as she interviewed a surgeon who was discussing modern extended mortality, and I thought about this thread...

One of the interesting statistics which I think certainly would have an affect on the increased incidence/new cases in the period labeled (3), above, is that THE AVERAGE LIFESPAN IN THIS COUNTRY HAS INCREASED 40 YEARS IN THE LAST CENTURY. That's an amazing statistic with so many ramifications on life and quality of life. But in regard to the period labeled (3), it seems highly likely (un-"provable") to be a direct contributor to increased cases.

------------------------------------------------

The surgeon made other interesting, notable comments. One that stuck with me compared the perspective of today's healthcare providers to those a perhaps 2 generations ago. His comment was that we have evolved from a "Doc knows best" to a "retail-model" of healthcare. While he did not specifically cite prostate cancer care, I think we've all seen these scenarios (and they are certainly well documented in the literature) where surgeons tell their patients "I can definately treat you," but the say little or nothing about the subsequent unfavorable quality of life impact. Many simply were not trained to have these discussions. People want to ask "What would you do?"—they want a counselor—but the doctor usually defaults to saying, "it's your decision." Once again, we need better patient education about PC...

|

|